The automaker smart is hoping to transform itself from misunderstood genius to mainstream success.

I’m drawn to the smart story, ethos, history—yes, even the cars—because the engineering concept was meant to provide affordable transportation for the masses, at low environmental cost from production to its end of life.

(Even if it ends as a cheap toy chewed up for YouTube views.)

Many people still own a smart fortwo and operate it as intended, as city cars, second cars, or because they simply like it. But not enough to ensure the smart concept’s survival.

The concept that enabled the smart cars didn’t just begin on a whim, in a design studio or focus group—but as a response to automotive manufacturing itself.

Problem? From its early work on city cars and its collaboration with Lebanese-Swiss watchmaker Nicolas Hayek, many decision-makers at key places in its parent company Daimler-Benz (then DaimlerChrysler, Daimler AG and now the Mercedes-Benz Group in a joint venture with Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co.) never seemed to understand it’s a smart first, and a ‘car’ second.

The 2023 smart #1 EV, by comparison, is a car first, and a smart second. How did this happen?

~

Long gone is the phonebooth-for-two layout, which props driver and passenger upright in traffic for visibility (and for jokes at the layman’s expense).

Visually, I love the echos of the fortwo’s plastic-heavy bodywork being echoed in the #1’s soft curves. That is about it.

The new car is only sold as an electric, and really—it’s Daimler’s rival to the MINI range and countless others that will emerge from Europe, Korea, and China in the next decade. There will be a Brabus-badged bruiser with approximately 400 horsepower, if the spy photos are to be trusted.

spy photos for the Brabus version • source as watermarked

I haven’t driven the new car, I haven’t seen it, but in all fairness…neither have many of the people who approved the car in the first place—as the #1 is simply not in large scale production yet.

What if…they had the winning vehicle recipe early on and overlords at Daimler-Benz, then DaimlerChrysler, Daimler AG—and now jointly—by Mercedes-Benz AG and Zhejiang Geely Holding Group have been foolishly overthinking their cupcake ever since?

I write with confidence: the best-selling electric vehicle in China—600,000 sold in less than two years 2020-2022—shares an eerily similar design brief with early smart models and prototypes from the early 1990s.

Let’s boil it down: cheap, electric (or hybrid), and fashionable. SAIC-GM-Wuling have nailed all three. A smart’s been lucky to ever meet one or two of those criteria.

I say: People don’t hate small cars. Profit-hungry automakers do.

~

Creating a profitable product is often not the same as creating a stylish, ecologically-focused, or popular one.

It is crucial to understand that smart (the car, company, and concept) was meant to root out many of these challenges at their core, by rethinking an entire history of mass production.

If executives who inherited the smart system weren’t inspired or capable enough to revamp production and expand the concept at scale, it matters not how good the cars may have been or how much owners cared.

Valued shareholders drive balance sheets at most large companies like Mercedes-Benz AG, and the time to repay investments is always ticking forward.

It—Swatch Mercedes Art, aka ‘smart’—was a huge project: development of the smart production methods, as well as the vehicles, are said to have been Europe’s most expensive private sector investment of the 1990s. The return on this investment was a loss, by 2013, of an estimated $4.6 billion Usd. and more than $500 million per year since.

Ghastly amounts, sure. But at around the same time, Daimler AG is said to have also lost an estimated $405,982 Usd. (inflation corrected) on each of the 3,000 Maybach ultra luxury sedans built from 2002-2013.

Though smart was losing ‘only’ an estimated $6,100 per car by late 2013, its higher production volumes committed the company to staggering losses not only to investors—but in market share and public support for the egg-like models.

“We are learning our first lesson in smart testing here: Americans are open to every baffling novelty…”

“…That the smart engine makes ends meet with three cylinders and a displacement of 0.6 liters leaves them speechless. That it unleashes 55 horsepowers for a top speed of 81 mph or 130 km/h generates admiration. And upon being told that a smart does 65 to 70 miles to a single gallon of fuel, they clap their hands – this is ‘incredible’ by American standards.”

– automotive writer Jürgen Zöllter, 1998

~

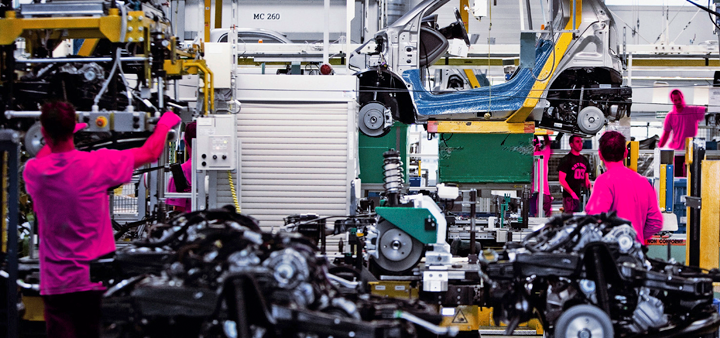

The smart fortwo we got was far from the usual way to build a car: metal presses. Robots. Paint booths. In-house production facilities. Shared components and platforms.

The major players battle by much of the same rule book for good reason: it’s highly profitable, pretty efficient, and reliable at scale.

What scale, indeed: the automotive industry comprises some of the most complex and impactful operations mankind has ever seen…for decades. It has done so since River Rouge was the topic of dinner conversation.

Comparing the scale of what it takes to build millions of your average pickup trucks or family crossovers only emphasizes how tiny production was at smartville, Hambach, France in comparison to many other car factories.

- In the first seven years of production (1998-2004), about 574,600 fortwos were built.

- In 1998 alone, Volkswagen sold 672,465 Golf models in Europe, plus more than 25,000 elsewhere.

Alright, maybe that’s not a fair comparison—what about the reborn Fiat 500, which hit the market in Europe in 2007? City car vs city car:

- smart sold 1,762 per week on average in 2007. Fiat? 1,019 per week.

Sounds like winning, until you realize that in 2007 the entire 500 production run was sold out in just three weeks.

(I cherry-picked these numbers before SUV and truck sales started ballooning in ~2010.)

It may have been simple in concept, but supplier contracts, transportation logistics, engineering sub-assemblies, developing inventory systems, plastic repair processes, sub 1-litre powertrains, a car sharing network, and even the PEZ-like dealership display boxes all stood against convention.

Company founders had invented the car—surely it could now reinvent it?

The smart fortwo, forfour, roadster, and coupé stayed anomalies, for a number of reasons that began in the boardroom.

Robots didn’t make smarts.

Would you believe me if I told you that the first two generations of smart fortwo were actually 98% handmade (on purpose)—partly to realize greater socioeconomic benefits in that region of Europe?

~

Daimler-Benz CEO at the time, Edzard Reuter, was said to be among the first business leaders in Germany to see a need to respect the environment and who was averse to chasing profits at too great a societal cost.

It is Reuter and a team of execs that started rolling this smart snowball more than 30 years ago.

First, chairman of the Board of Management of Mercedes-Benz AG, Werner Niefer, met Swatch visionary Nicolas G. Hayek about his company’s small car aspirations in 1992.

Niefer laid the blanket and tasked his successor, Helmut Werner, with setting up this picnic. For good reason: between 1992 and 1993, Mercedes-Benz had already commissioned a brand-new California design studio and tasked its designers with developing a Los Angeles-worthy city car.

Mercedes-Benz Micro Compact Car (MCC) project manager / designer Johann Tomforde and Member of the Board of Management, Passenger Car Division, Daimler-Benz AG—aka Mister Mercedes—Jürgen Hubbard were other key figures in making the early work happen.

Reuter, Niefer and Werner’s teams merged development of the Swatch team’s contributions and Hayek’s feedback, then established a joint venture, Micro Compact Car Smart GmbH, that split work based on each group’s strengths.

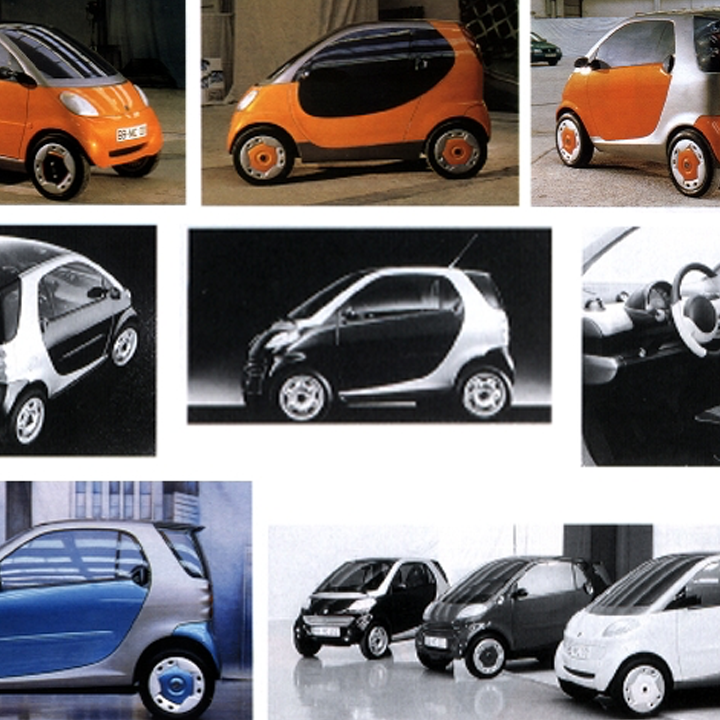

early concepts for the smart; note the off-road version in top left • source Mercedes-Benz Group

~

In 1995, however, Werner lost out to Jurgen Schrempp for control of the overall Daimler-Benz company.

At the time, Schrempp was a manager at Daimler-Benz subsidiary, Deutsche Aerospace AG (DASA). The management team decided Schrempp was the ideal leader between the two in returning the group to profitability. (I’m snickering, if you’re curious.)

No problem—the MCC project had been approved by the Mercedes supervisory board and it was picking up steam.

Is there proof Schrempp even knew about the smart, let alone cared for anything but its success? David Woodruff, reporting for Bloomberg, wrote in early 1997:

Schrempp, 52, launched his first major challenge to Werner before he had officially succeeded Edzard Reuter as Daimler CEO in May, 1995. That spring, he demanded a review of Wer-ner's pet project, the $10,000 SMART microcar, a daring joint venture with Swiss watchmaker SMH Swatch. […] Werner finally silenced criticism in May, 1995, by inviting Schrempp and other Daimler board members to drive the SMART at the dome-shaped building in suburban Stuttgart, where Mercedes executives view future products. They loved it.

– bloomberg.com

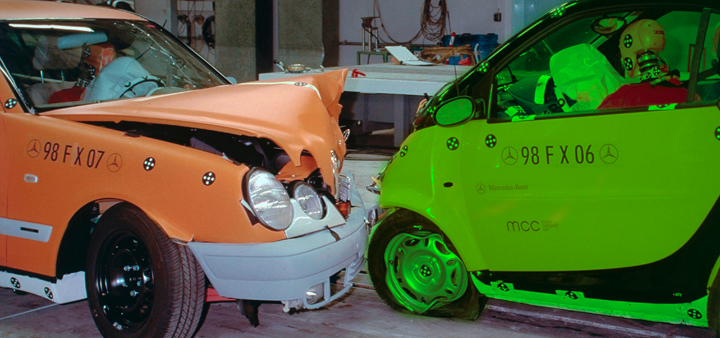

Within months of the fortwo’s eventual launch in 1998, Schrempp then had to expensively, publicly, approve last-minute stability controls being added to the smart car because of safety concerns following early fumbles with the dissimilar in all but size Mercedes A-Class 5-door hatchback.

Still with no models on the market, Schrempp then approved a buyout of Micro Compact Car Smart GmbH, purchasing shares held by Swatch parent company Société de Microélectronique et d'Horlogerie (SMH) to bring smart fully under Daimler-Benz control.

What few knew at this point is that Schrempp’s much grander aspirations in the name of shareholder value were now mere weeks from being realized. His longtime colleague-turned-mistress-turned-personal assistant, Lydia Deininger, was by his side as the finishing touches were placed on the deal certain to stamp Schrempps legacy on the German business elite.

Fifty-six days before smart fortwo production started on July 2, 1998, Schrempp announced he’d be the co-CEO of a new automaker: DaimlerChrysler AG.

Let us join the afterparty, courtesy of this outstanding story written by Bill Vlasic and Bradley A. Stertz, published in Bloomberg more than a year into the partnership:

Ties and coats were shed and shirtsleeves rolled up. Schrempp and the group bellowed song after song until the wee hours. The German co-chairman led one final chorus of "Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie." Then, with a wild gleam in his eye, Schrempp grabbed his ever-present assistant, Lydia Deininger, picked her up, and threw her over his shoulder.

The room exploded in laughter as Schrempp snatched a bottle of champagne in his free hand, raised it in the air, and yelled out with a grin: "See you later, boys!" Then he carried her off, not to be seen for the rest of the night.

Later in the story, reporting confirms his colleagues soon connected the dots:

The Chrysler execs soon realized that Lydia Deininger was far more than Schrempp's secretary and companion. The petite brunette sat in on every high-level meeting, taking notes, producing documents, and placing a Marlboro in Schrempp's hand when he waved it a certain way. […] Executives in Auburn Hills just weren't accustomed to a married CEO openly carrying on a relationship with his attractive assistant.

– bloomberg.com

Another questionable move made shortly after the merger in 1998 was canceling Chrysler’s innovative and environmentally sensitive Composite Concept Vehicle (CCV), a Citroën 2CV-inspired model for emerging markets featuring a composite plastic body shell to be assembled in two halves, like a walnut.

Already in an advanced stage of development after its unveil as a show car a year earlier, the 4-door car had a number of similarities with the eventual smart fortwo and forfour range, including paint hues moulded into the bodywork, cheerful styling, retractable canvas roof, and narrow tires. Was the CCV the real deal? We’ll never know.

I do know that once DaimlerChrysler finally committed itself to believing its approach was the right one, the relative few cars and flashes of potential that did emerge from smartville were miraculous in context of how they happened in the first place.

Just two years after the merger in November 2000, New York Times journalists Edmund L. Andrews and Keith Bradsher would write the following:

“Mr. Reuter nearly ruined Daimler by trying to make it an integrated ''technology'' company. Now Daimler is reeling from Mr. Schrempp’s attempt to make it the world’s dominant car company.”

A first working all-electric prototype with in-wheel hub motors, a stripped-out Citroën AX hatchback, was demonstrated in 1993 at a skating rink.

Executives—including then-development manager Dieter Zetsche—only saw their team struggle. It was a failure that galvanized the Germans against allowing the Swiss to be in charge of the microcar’s movement.

~

Just ask Bertha Benz: even without boardroom drama, trailblazing is tough.

Back in the 1990s, two decades before China became a vehicle manufacturing powerhouse and nearly three before EV components had matured—most of which touch supply chains in Asia—it wasn’t possible to sketch a ’skateboard’ chassis, electric motors, or the components needed without inventing most of it first.

The time between that first Citroën AX-based in-wheel hub motor prototype and the first hybrid smart fortwo? 14 years. All-electric smart fortwo models in regular production? 16 years.

Fast forward to June 2020, and SAIC-GM-Wuling had the MINI EV on sale after 12 months of development work.

Add in executive changeover, mergers, global financial crisis, and even watching its engines being trounced most Formula 1 weekends during that time and it’s no surprise reality diverged from the expectations of everyone atop the very merry Dai-Chry-Mer-Benz & Co.

Without the driveline to support the scale production of a safe, inexpensive, electric (or hybrid) city car, the group nevertheless plowed ahead, believing the smart concept could help realize improvements elsewhere and engender good PR with enviro-mentals.

Diverging from the original MCC / SMH electric car plans in the early ’90s, however, seems to have put the smart car at odds with the smart concept. When you reach the point of realizing you can’t create what you first imagined, do you stop, pause, or push?

Nicolas Hayek died less than a year after the electric smart went on sale in late 2009. He was 82.

early crash test of the MCC, left; smartville from above, right. • source Mercedes-Benz AG

If you can’t build a car close to the original design brief, why then double down, invest in, and spin up an entirely new €450 million production facility in Middle-of-Nowhere, France? Having faith in the smart and being fiscally smart aren’t the same thing.

As a car dork, I’m personally grateful they moved heaven and earth to make it happen, but even I’ll admit that few of my decisions over 38 years have been celebrated for their good financial sense.

Consider smart’s balance sheet, however, and it’s clear that even very highly-paid experts didn’t know what to do within the operating window of corporate governance.

The smart—er, Swatch-mobile—was originally conceived by Nicolas G. Hayek to be all electric.

Then, as development progressed, then a hybrid. It launched powered by gas or diesel.

these early microcars are Mercedes-Benz developed—in Los Angeles no less—before a partnership with Swatch • source Mercedes-Benz Group

~

Industry analysts have estimated that its parent company lost between $4,500 and $6,100 per smart.

Is it any wonder, then, that when the balance sheet left nothing to hide, those in charge began scrambling for something—anything—that could have turned the tide before financial pains began to smart?

Note a portion of that New York Times quote from the year 2000, but in the context of 2022: “Mr. Reuter nearly ruined Daimler by trying to make it an integrated ''technology'' company.”

As firms like Apple, Nintendo, Google, Meta, and others have proven, creating an integrated technology company can be highly profitable. Thirty years ago, Reuter was derided by the German business press and his own board for thinking an automaker and space satellite builder could exist under the same corporate umbrella. Now, Elon Musk and Tesla are reaping the rewards of doing the same.

Funny. On the Mercedes-Benz website right this second, its technology page proudly states:

“As a company founded by engineers, we believe technology can also help to engineer a better future. Our way to sustainable mobility is innovation – in a holistic approach along the entire value chain.”

~

Our low-calorie compact car cake is nearly iced and ready to eat; why aren’t you as excited as I am?

To many, smart and its models are immediately dismissed as a joke, so I wanted to set the stage on main players and smart itself before geeking out on the cars themselves in part II.

Shipping production off to China and basing the all-electric smart #1 lineup on a skateboard chassis may sound like a natural evolution toward the light of profitability, but I have concerns: the vehicle concept must come first. Although the new car is closer in technology to smart’s origins as a practical EV, that’s where the similarities end.

The challenge of developing the so-called ‘smartville’—and the ideals of minimizing and optimizing production wherever possible with Swiss-like precision—won’t be a feature of Geely’s plans. smart #1 is based on the Geely-developed Sustainable Experience Architecture, a system of building electric vehicles that will cover anything from entry-level models (SEA-E) to sports cars (SEA-S) and commercial vehicles (SEA-C).

It may lead to some awesome vehicles, but it’s too early to tell—and that’s the point. The smart concept has been reinterpreted as a mere wrapper for SEA2, not as the car.

~

“BUT!!! WHO CARES, PEOPLE STILL HATE small CARS!! They’re dead! Why get a smart when the Civic has better fuel economy? Why get a smart EV when you can only go 100kms? AND small CAR SALES HAVE BEEN SHRINKING!!”

You’re so polite to get this far without shouting that, thanks. I ask and answer for you—have there been many compelling, affordable small cars worth recommending—not really. Companies don’t want the hassle.

Why? They’re just not very profitable.

However, proven by curious onlookers during smart fortwo tests in the U.S. in 1998, the successful MINI EV in 2022, and countless other examples: I’m not alone in loving small cars like the smart fortwo.

If you have the means, my advice is to indulge early and often in your passion for minimal motoring—stock up on tin cans while you’re able to, prepper—because even the most promising small car plans can snowball into boardroom-sinking icebergs.

Footnote1

Neither here nor there, but if you’re a modern office worker and wondering about the HR implications than yes: she a coworker of his from 1990. And Schrempp promoted her along with him, now as an office manager working from headquarters in Stuttgart, when he was made CEO in 1995. They married in 2000, and she stayed on at Daimler after his departure in 2006.

The only reason we know how this ended? The German business newspaper, Handelsblatt, devoted an entire article to her in 2008 on her departure: Das „Hexle“ räumt bei Daimler das Feld, loosely, ‘The “Witch” clears the field at Daimler.’

• Martin Buchenau: “Das „Hexle“ räumt bei Daimler das Feld” – 2008 (handelsblatt.com)

Sources

- Michael Banovsky: “Get to know the Wuling Hongguang Mini EV” – 2022 (speedster.news)

- Jonathan Lee: “Geely SEA EV architecture detailed – 5 versions to cover all sizes, including sports cars and pick-ups” – 2021 (paultan.org)

- Laura Cozzi and Apostolos Petropoulos: “Global SUV sales set another record in 2021, setting back efforts to reduce emissions” – 2021 (iea.org)

- Mercedes-Benz AG: Annual Report – 2020 (.pdf)

- „Ein ‚Weiter so‘ wie vor der jüngsten Krise wird es nicht geben!“ (“There will be no 'business as usual' as before the recent crisis!” - Interview with Prof. Tomforde) – 2020 (nachhaltigkeitspreis.de)

- Georg Kacher: “Why Maybach closed: Daimler lost €330,000 on each one” – 2012 (carmagazine.co.uk)

- Nick Holt: “Size me up, smart” – 2008 (automotivemanufacturingsolutions.com)

- Mercedes-Benz AG: official smart history press kit – 2007 (group-media.mercedes-benz.com)

- Mercedes-Benz AG: 'Cooperation of Swatch and Mercedes-Benz' – 2007 (group-media.mercedes-benz.com)

- James P Warren and Ed Rhodes: “‘Smart’ Design: Greening the Total Product System” Greening the supply chain, Springer Verlag UK, pp. 271–291. – 2006 (.pdf)

- various: Helmut Werner, 67; Former Chairman of Mercedes-Benz – 2004 (latimes.com)

- Bill Vlasic and Bradley A. Stertz: “Taken for a ride” – 2000 (bloomberg.com)

- Edmund L. Andrews with Keith Bradsher: “This 1998 Model Is Looking More Like a Lemon” – 2000 (nytimes.com)

- Denis Staunton: “Reuter reflections spill the Daimler beans” – 1998 (irishtimes.com)

- David Woodruff: “Dustup At Daimler” – 1997 (bloomberg.com)

- John Templeman: “The New Mercedes” – 1996 (bloomberg.com)

- Wikipedia: Smart '1' (wikipedia.org)

- MoMA: ‘Smart Car ("Smart & Pulse" Coupé)’ (moma.org)

Member discussion