Dubonnet Dolphin

Car of the Day #62: 1936 Dubonnet Dolphin

Please indulge me as I write about André Dubonnet. Wealthy heir to the founder of the Dubonnet aperitif, André grew up in relaxed, upscale, privileged surroundings.

His brother was one of the first people to fly over Paris in an airplane; the family was apparently naturally attracted to machines. Dubonnet soon found himself in the military—and shortly after, in the most advanced machines possible: airplanes. Getting above enemies is a clear tactical advantage (provided you’re not shot down, of course) and Dubonnet found himself in the French balloon corps in 1916, before joining the first French Air Service aviation group in 1917.

Honoured for his prowess in the sky, he soon found himself behind the wheel of some of the era’s fastest race cars. With use of both an Hispano-Suiza and Bugatti, he quickly began to claim victories, including at the old Monza circuit. In his Monza triumph, he completed 40 laps (400 km or 248 miles) of the fearsome circuit, averaging 131 km/h (82 mph).

All without a seatbelt, natch.

With the means to acquire and an attitude to wring the necks of the fastest machines of his era, he upgraded to a 1924 Hispano-Suiza H6 C affectionately named “Tulipwood.” Its streamlined tulipwood bodywork over an aluminum hull was made by French aircraft manufacturer Nieuport, and could be considered the Pagani Zonda of its day: fast, sexy, and made from unconventional and experimental materials. Entering it in the 1924 Targa Florio, he finished sixth.

His strong performances earned the attention of Bugatti, who sold him a car and offered manufacturer support, an offer he accepted. After winning the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1928 for the famed marque, he retired from racing at 31. (Then went to represent France at the second-ever Olympic bobsleigh event.)

After his time racing, Dubonnet spent the rest of his life trying to push the automobile into the future. Rarely does a company, much less a private individual, spends considerable resources on largely untested theories—but that’s exactly what Dubonnet hoped to accomplish with the development of streamlined vehicles.

Then, recognizing he lacked the resources or the desire to compete directly against Auto Union’s streamlined land speed record machines at that time, Dubonnet instead sought to make passenger cars both faster and more efficient.

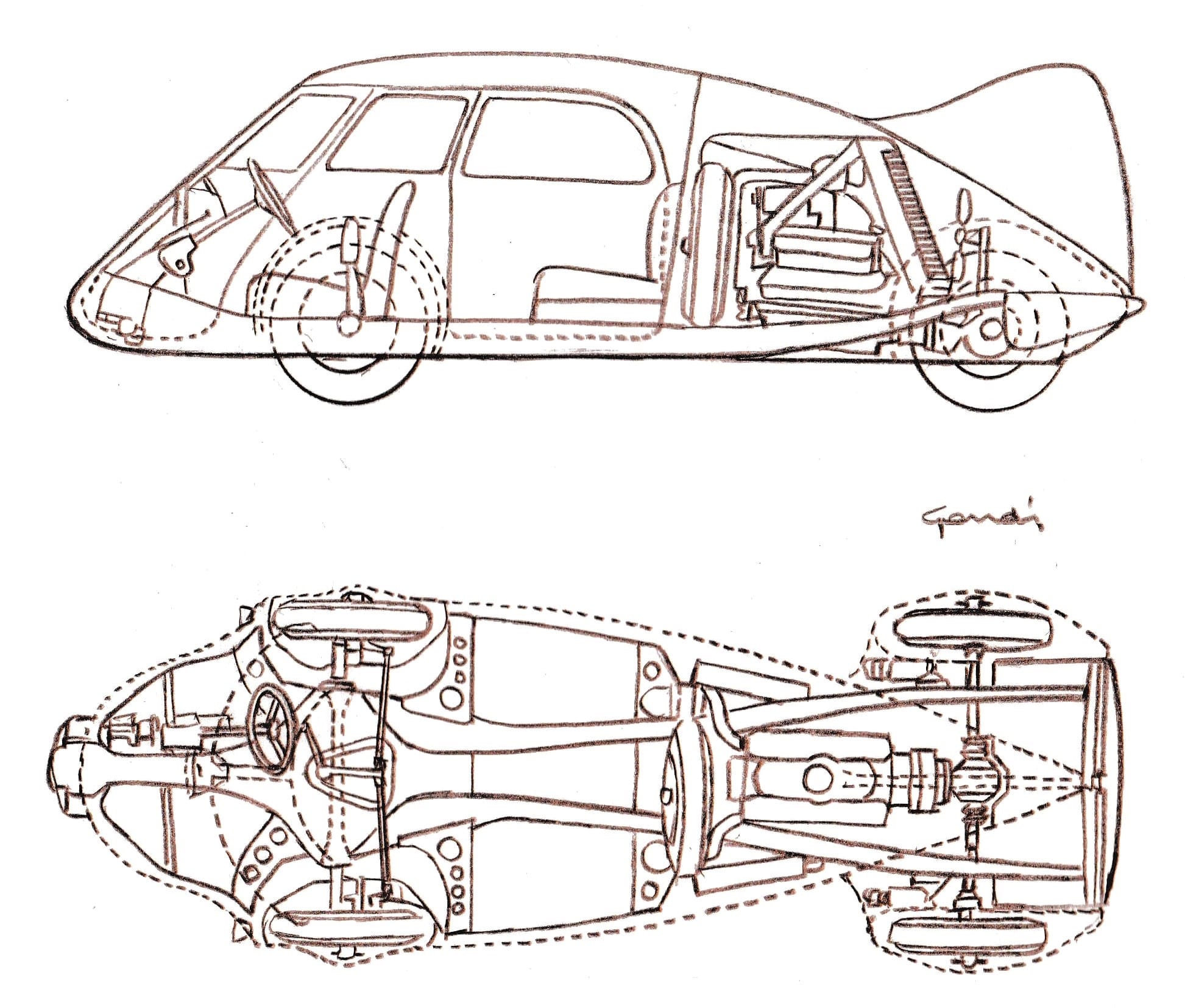

Dubonnet started with a backbone chassis similar to the one Colin Chapman would later popularize, then mounted a Matford (Ford) 3.7-litre V8 in the middle, making this, yes, a V8-powered mid-engined sedan.

He turned to the prominent Paris-based American designers Hibbard & Darrin (Darrin would later give us the Kaiser-Darrin sports car) to pen his dream machine. Dubonnet and Darrin must have quickly found themselves on common ground; Darrin had also been an ace pilot and spent his free time playing polo.

During the day, Hibbard & Darrin constructed many incredible vehicles for the world’s elite using the best chassis—Minerva, Voisin, Delage, Bugatti, Packard, Stutz, Duesenberg, Isotta-Fraschini, Maybach, Rolls-Royce, etc.—of the era. Alfred P. Sloan later picked Hibbard to lead the Cadillac design studio.

After the stock market crash in 1929, Hibbard & Darrin quickly folded, with Dubonnet taking the Dolphin project to Darrin’s new venture, the Paris-based Carrosserie Fernandez et Darrin.

As coachbuilt.com notes, “…decisions at Fernandez & Darrin were made with an absolute disregard for cost. Beauty, utility, and safety were the firm’s prime considerations, so it’s not surprising that a staff of 200 produced less than ten finished bodies per month. Darrin recalled that most of the firm’s sales were in the 125,000 to 1,000,000 francs range, roughly $10,000 to $40,000, depending on the body style and whether the customer supplied the chassis or not.”

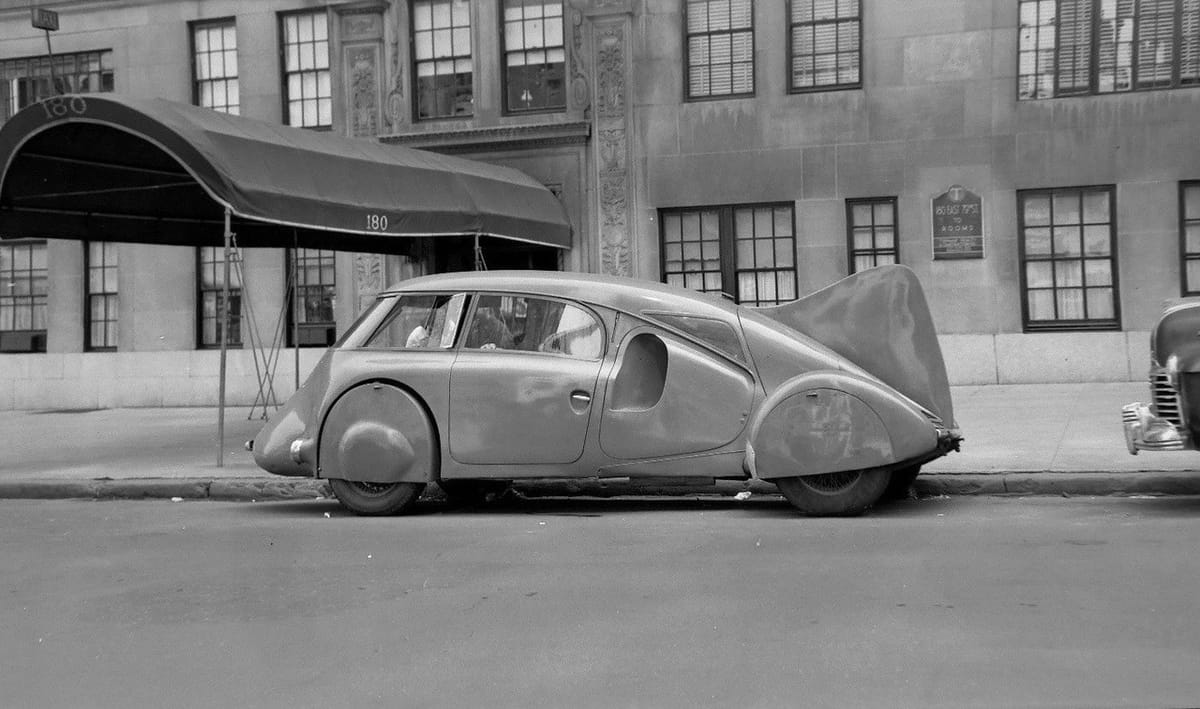

When finished in 1936, I can imagine the Dolphin costing a literal arm and leg, but the upshot was an incredibly well-finished streamliner that looked a world apart from everything else built up to that point. The front doors were hinged in the middle of the body, sort of like an Iso Isetta, with a pair of conventional doors behind.

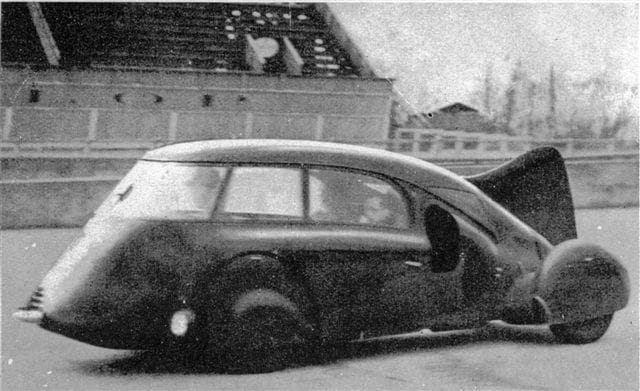

Its aircraft connections are undeniable, with a single tailfin to aid in high-speed stability and rear wheels covered in aerodynamic pods. This was no trailer queen, however. Given Dubonnet’s wealth and racing successes, the car was engineered to perform with the world’s best.

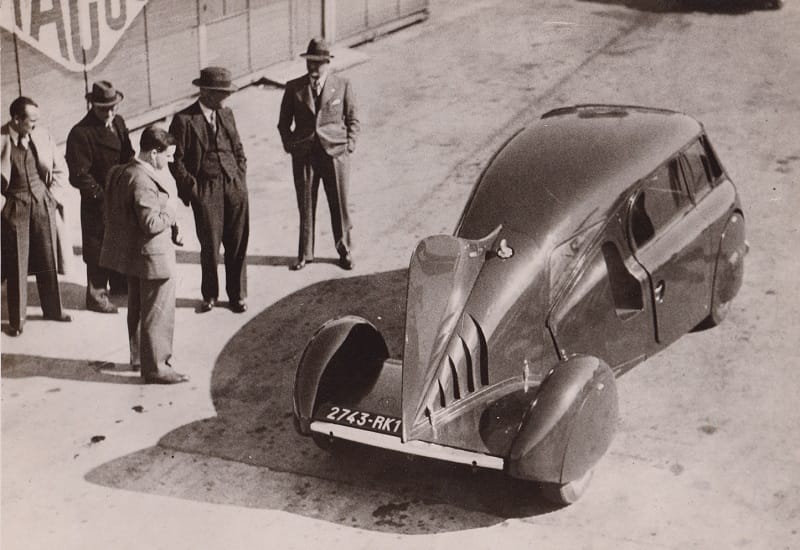

After its completion, Dubonnet took the car to the L'autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, the dangerous high-speed ovoid bowl that claimed the life of Alberto Ascari’s father, Antonio, during the first race held at the track. The Dolphin would square off against a standard Ford sedan equipped with the same engine as part of some high-speed testing.

The standard sedan topped out at 131 km/h (82 mph) and averaged 15.6 L/100 km (15 US mpg), while the Dolphin was good for 173 km/h (108 mph). Fuel consumption was just 10.7 L/100 km (22 US mpg).

The racer soon shipped his creation to Detroit, showing it to both General Motors and Ford as a possible design for cars of the future. Both car companies were uninterested, and the fate of the (nearly) revolutionary Dolphin is unknown…

In fact, the first photo in this article is one of the last-known images of the car, purported to have been taken as late as 1939.

What’s your take on this early streamlined car — far ahead of its time or doomed to fail from the start?

SUPPORTING MEMBERS

Thank you to my supporting members: Ben B., Brad B., Chris G., Daniel G., Damian S., Daniel P., Ingrid P., Karl D., Luis O., Michael J., Michael L., Michelle S., Mike B., Mike L., Mike M., Richard W., Sam L., Wiley H.